Designing the In-Between

The unique potential of alleys as designed spaces

An editorial by Gaelle Gourmelon, MKSK Associate, Designer, Washington, DC.

Not a day goes by when I don’t think about alleys. When I park behind our office, I ogle the trundling trash and delivery trucks as though I’ve learned a secret tucked behind the neighborhood’s polished façade. As I walk past rows of backyards in my neighborhood, I feel a small rush of adrenaline akin to trespassing, despite my very legal wanderings. These location-specific moments are a feast for a designer’s mind.

Scenes like these happen because alleys exist as wonderfully liminal spaces. They are shared but sized to a human scale. They feel vestigial but are often claimed by those who see their potential. They are gritty but inspire a sense of comfortable familiarity. They are hidden but ubiquitous in many American cities.

At MKSK, we’ve taken inspiration from alleys and delivered reimaginations of these often-overlooked corridors. Here is a look at some of my favorite alley evolutions:

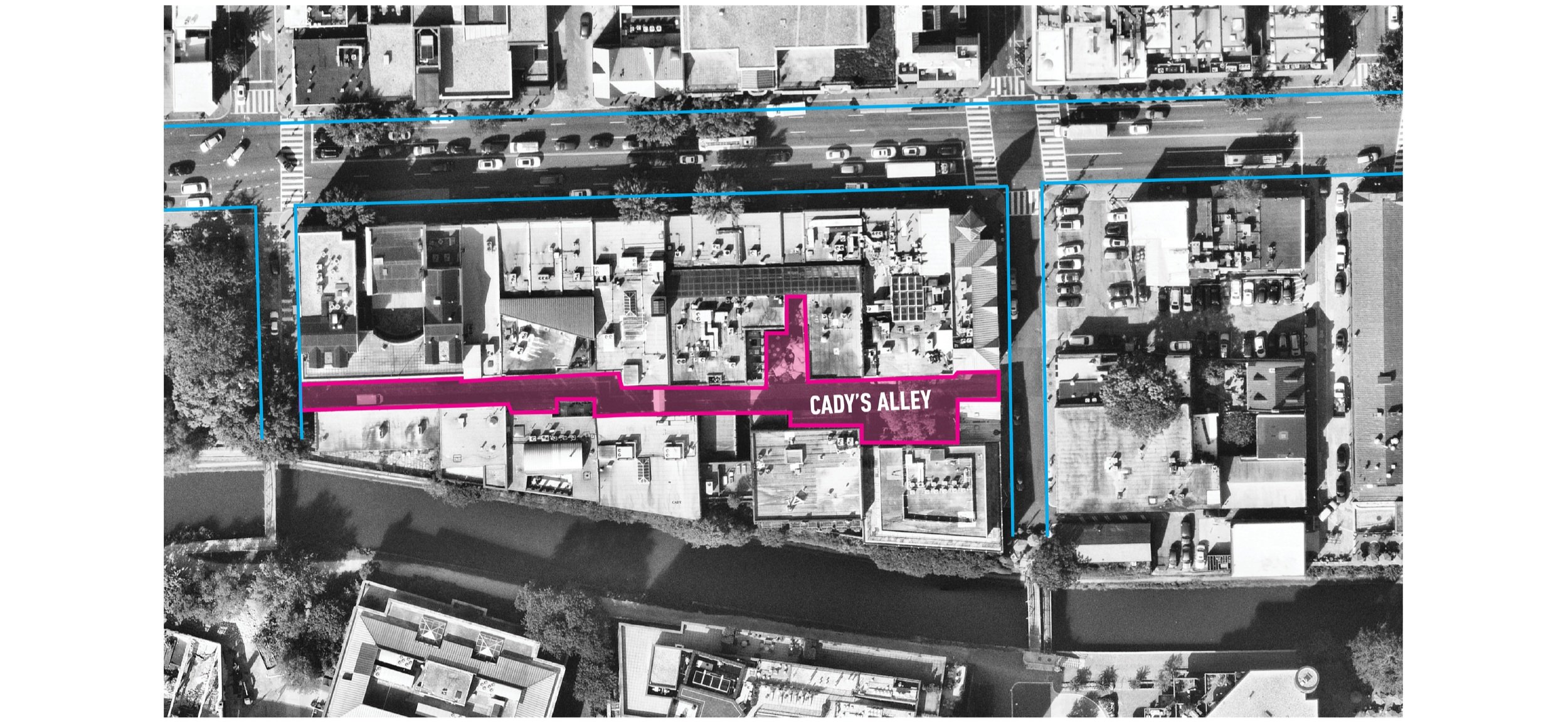

Shared, but on a human scale: CADY’S ALLEY

Washington, District of Columbia

Just a half-block away from the bustling, six-lane M Street Corridor of Georgetown in Washington, D.C., MKSK’s design for Cady’s Alley brings all its constituents – shoppers, residents, drivers of service vehicles – together while celebrating what makes alleys unique.

Why it works: The shared nature of alleys, combined with their relative narrowness, gives them connective potential that other urban spaces can’t provide. In Cady’s Alley, some stretches are just 20 feet wide. The spatial rhythm of nearby doors and windows, as well as the sound of cobbles, help drivers gauge speed. The slower pace in Cady’s Alley means that cars can access the places they need (like parking or drop-off areas) without endangering pedestrians.

Unique to alleys is also their center drainage. Because stormwater doesn’t drain to the sides of the street (where a curb would be on most urban roads), there is no need for raised sidewalks to direct stormwater. This allows the full expanse of the alley to receive mixed-use paving, encouraging people to meander and pause by eliminating the dreaded “excuse me, you’re blocking the sidewalk” moments along retail corridors. Combined with the alley’s compact scale, continuous paving means that visitors only need to take a few ambling steps to go from café to storefront.

Vestigial, but full of potential: WALNUT HILLS FIVE POINTS

Cincinnati, Ohio

At the interface of a historic commercial district and urban residences, not far from what was once the center of commerce for Black-owned businesses and civic life in Cincinnati, there existed a void. The Walnut Hills community, however, saw this empty confluence of alleys as an opportunity.

In coordination with the Walnut Hills Redevelopment Foundation and MKSK’s Community Impact Studio, the community envisioned, prototyped and ultimately built an inclusively programmed space where musicians, food vendors and local microbreweries can now host events. Through a thoughtful treatment of the ground, the reuse of salvaged materials, competition-based public art installations at the five gateways, and the introduction of overhead lighting, the space has become a shared living room for the neighborhood. Today, Cincy Nice, a Black-forward community group, manages and programs the Five Points space.

Why it works: Alleys are often unclaimed by residents or businesses around them, especially in areas with vacancies. They can feel like leftover space and be left to fall into disrepair. Surprisingly, that lack of clear claim is also alleys’ secret strength. When activated as a community space, alleys can accommodate immense flexibility and absorb many identities. They are not burdened by prescriptive esthetics nor clearly defined in program. Nestled in the center of a block, they can serve as a communal space that evolves with the needs of the surrounding residents and businesses. This alley, located at the intersection of several alleys, enables a symbolic and literal feeling of gathering.

Urban, but familiar: EASTON URBAN DISTRICT

Columbus, Ohio

When the Easton Urban District opened in 2019, a 250,000 square foot mixed-use expansion to 20 year old Easton Town Center, materials set the tone for the new arts and entertainment district. Corrugated panels, weathered steel and a yellow glazed reclaimed masonry brick crown a narrow walkway connecting restaurants, bars and entertainment venues. Despite the district’s newness, a story arises from the unexpected confluence of landscape elements.

Why it works: Materials have a way of triggering stories. A massive, industrial chimney created by local artisan Anthony Ball, signals the passage of time. A circular pattern of new and reclaimed brick gives the sensation there was a decision and a hand that created it. Murals creep over building materials. On the chimney base, exposed brick stamps reveal a maker and location. The alley’s tight space forces an intimate encounter with its materiality as one walks through. Its forced adjacencies and layering hold each material in dialogue with those around it. Despite the alley’s relative youth and the unexpectedness of its materials, it holds a familiar air.

Hidden, but ubiquitous: TEMPERANCE AVENUE

Washington, District of Columbia

Unlike me, most District residents likely don’t spend their time thinking about alleys. For many Washingtonians, alleys are simply places in which to hide a parked car or trash bins, dodging a few rats along the way. But when Washington’s street grid was first laid out into large blocks, alleys quickly became an important part of the urban fabric. Early developers incorporated service alleys in most blocks to allow access to kitchens, stables and other dependency buildings that were part of daily life.

As housing demand grew, alley dwellings started to emerge and, after the Civil War, hundreds of alleys hosted bustling communities of freed Black residents. Continuously underserved by sanitation infrastructure and eventually becoming overcrowded, alley dwellings were made illegal and mostly destroyed due to health concerns fueled by racial prejudice. Temperance Avenue, hidden mid-block along the bustling “Black Broadway” U Street Corridor, was one of these close-knit “blind alleys.” Today, with modern improvements, MKSK is helping to design a return to historic alley living.

Why it works: The District has responded to a housing shortage and calls for meaningful development by making alley dwellings legal again. Within the District, there are 46 linear miles of potential alley frontage, translating to tens of thousands of opportunities for new housing and recreation spaces within existing city blocks. The design for the new Temperance Avenue proposes a return to a townhouse scale and incorporates a discrete walk that transitions from the urban grid to a residential enclave. Murals, historic signage, and art celebrate what was once a vibrant community.

You will always find me peering around corners, exploring alleys as the connective tissue between the places where we live our lives. Alleys are spaces that force negotiation and connection. These transitional spaces hold lessons for how we can design within blurred edges—how we can introduce novelty by taking inspiration from spaces that are, at their core, somewhat undefined.

Want to learn more about our other alley (and alley-inspired) projects?

Imagination Alley – Cincinnati, Ohio

The Fish Market – Washington, District of Columbia

Bridge Street District – Dublin, Ohio

Ludlow Alley – Columbus, Ohio

Cady’s Alley - Washington, District of Columbia

Walnut Hills Five Points - Cincinnati, Ohio

East Urban District - Columbus, Ohio

Gaelle Gourmelon is an Associate and Landscape Designer at MKSK. With a background in biology and public health, she approaches landscapes as a set of living and social systems that respond to material, scale, and function.